Money supply, often dubbed the lifeblood of economies, serves as the cornerstone of modern financial systems. It represents the total stock of money within an economy at a given point in time, playing a pivotal role in shaping economic activity, inflation, and interest rates.

Understanding its dynamics is essential for policymakers, economists, investors, and the general public alike. Here below are different definitions of money supply by various authors:

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is Money Supply | Different Definitions

- Classical Economists: In classical economics, money supply refers to the total amount of currency in circulation along with demand deposits held by commercial banks. This definition emphasizes the tangible forms of money circulating in the economy.

- Keynesian Economists: Keynesian economists expand the definition of money supply to include not only physical currency and demand deposits but also other highly liquid assets such as savings deposits and money market funds. This broader definition reflects the importance of various forms of money in influencing economic activity and aggregate demand.

- Monetarist School: Monetarist economists, following the ideas of Milton Friedman, define money supply more narrowly, focusing primarily on the monetary base or high-powered money, which includes currency in circulation and bank reserves held at the central bank. They argue that changes in the money supply directly influence nominal GDP and inflation over the long run.

- Modern Monetary Theory (MMT): Proponents of Modern Monetary Theory define money supply in a broader context, incorporating not only government-issued currency but also bank-created money through the extension of credit. This perspective emphasizes the endogenous nature of money creation within the banking system and the role of government fiscal policy in managing the economy.

- Austrian School: Austrian economists tend to emphasize the importance of sound money backed by a commodity such as gold or silver. From this perspective, money supply refers to the total quantity of money that is backed by a tangible asset, ensuring its stability and intrinsic value.

- Financial Economists: From a financial perspective, money supply can be seen as the total amount of liquidity available in the financial system, including not only traditional forms of money but also other financial assets such as stocks, bonds, and derivatives. This definition highlights the interconnectedness of financial markets and the role of liquidity in shaping asset prices and market stability.

Each of these definitions reflects different theoretical perspectives and priorities within the field of economics, underscoring the complexity and multifaceted nature of the concept of money supply.

Depending on the context and analytical framework, economists may adopt different definitions to suit their specific research objectives and policy recommendations.

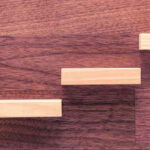

Different Types of Money Supply

Here below are the different types of money supply. Let’s discuss them one by one in detail below.

-

M0 (Base Money or High-Powered Money):

M0 money supply represents the most liquid form of money in an economy and consists of physical currency (coins and notes) in circulation and reserves held by commercial banks at the central bank.

Physical currency includes coins and banknotes issued by the central bank and held by individuals, businesses, and financial institutions. These are tangible forms of money that can be used for transactions.

Reserves refer to the funds that commercial banks are required to hold with the central bank to meet regulatory requirements and facilitate interbank transactions. These reserves are crucial for maintaining the stability and liquidity of the banking system.

-

M1 (Narrow Money):

M1 money supply encompasses a broader range of highly liquid assets that are readily accessible for transactions. It includes physical currency in circulation, demand deposits held by commercial banks, and other checkable deposits.

Demand deposits are funds held in checking accounts that depositors can access on demand without prior notice, typically through checks, debit cards, or electronic transfers. These accounts facilitate day-to-day transactions and payments.

Other checkable deposits include savings accounts or money market deposit accounts that offer check-writing privileges and allow for easy access to funds. While slightly less liquid than demand deposits, they still serve as readily available forms of money for transactions.

-

M2 (Broad Money):

M2 money supply represents a broader measure of money supply that includes M1 along with additional less liquid assets that can be quickly converted into cash or used as a medium of exchange.

In addition to the components of M1, M2 includes savings deposits, time deposits (certificates of deposit or CDs) with maturities of less than one year, and money market mutual funds (MMMFs).

Savings deposits are interest-bearing accounts held with commercial banks or thrift institutions, providing a secure place for individuals to save money while earning a modest return.

Time deposits, such as CDs, involve funds deposited with a bank for a fixed period at a specified interest rate. These deposits are less liquid than demand deposits but offer higher interest rates as compensation for locking in funds for a predetermined period.

MMMFs are investment funds that pool money from individual investors to purchase a diversified portfolio of short-term debt securities such as Treasury bills, commercial paper, and certificates of deposit. While not as liquid as demand deposits, MMMFs offer higher returns and stability compared to other investment options.

-

M3 (Broadest Measure of Money Supply):

M3 money supply represents the broadest measure of money supply, encompassing M2 along with additional less liquid assets that serve as store-of-value and medium-of-exchange functions.

In addition to the components of M2, M3 includes large time deposits (CDs) with maturities of more than one year and institutional money market funds.

Large time deposits involve funds deposited with financial institutions for longer durations, typically exceeding one year. These deposits offer higher interest rates than shorter-term CDs but entail greater liquidity risk due to the longer lock-up period.

Institutional money market funds are similar to MMMFs but cater to institutional investors such as corporations, pension funds, and government entities. These funds invest in short-term debt securities and provide investors with a convenient and low-risk option for managing cash reserves.

Understanding the various types of money supply is crucial for policymakers, economists, and investors to analyze the liquidity and stability of the financial system, monitor changes in monetary aggregates, and formulate effective monetary policy responses to economic developments.

Components of Money Supply

Let’s explore the components of money supply in detail:

-

Currency in Circulation (C):

Currency in circulation refers to the physical cash or coins issued by the central bank and held by individuals, businesses, and financial institutions.

This includes banknotes and coins that are actively used for transactions in the economy, whether for everyday purchases, wages, or business transactions.

Currency in circulation serves as a tangible form of money that facilitates transactions and acts as a medium of exchange, allowing individuals to buy goods and services without the need for electronic transactions or checks.

-

Demand Deposits (D):

Demand deposits are funds held in checking accounts at commercial banks and other depository institutions that can be accessed by depositors on demand without prior notice.

These accounts typically allow depositors to make withdrawals and payments using checks, debit cards, or electronic transfers, providing a convenient means of accessing funds for day-to-day transactions.

Demand deposits play a crucial role in the payment system by facilitating the transfer of funds between individuals, businesses, and financial institutions, thereby supporting economic activity and commerce.

-

Savings Deposits (S):

Savings deposits are interest-bearing accounts held with commercial banks, savings banks, or thrift institutions, where depositors can store funds for future use or emergencies.

Unlike demand deposits, savings deposits may have restrictions on the number of withdrawals or transfers allowed per month, as they are designed for longer-term savings rather than frequent transactions.

Savings deposits offer depositors a safe and secure way to accumulate funds while earning a modest return through interest payments, making them a popular choice for individuals seeking to build savings and financial resilience.

-

Time Deposits (T):

Time deposits, also known as certificates of deposit (CDs), are interest-bearing accounts where funds are deposited with a bank or financial institution for a fixed period at a specified interest rate.

These deposits typically have maturity periods ranging from a few months to several years, during which depositors cannot withdraw funds without incurring penalties or forfeiting interest.

Time deposits offer higher interest rates compared to savings deposits, reflecting the commitment of depositors to lock in funds for a predetermined period and the reduced liquidity risk for banks.

-

Money Market Mutual Funds (MMMFs):

Money market mutual funds are investment funds that pool money from individual investors to purchase a diversified portfolio of short-term debt securities such as Treasury bills, commercial paper, and certificates of deposit.

These funds offer investors a low-risk option for managing cash reserves while earning a competitive return compared to traditional savings or checking accounts.

MMMFs provide liquidity, safety, and diversification benefits to investors, making them an attractive alternative to other short-term investment options such as savings deposits or time deposits.

Understanding the components of money supply is essential for analyzing the liquidity and stability of the financial system, assessing changes in monetary aggregates, and formulating effective monetary policy responses to economic developments.

Central banks and policymakers closely monitor these components to gauge the health of the economy and implement measures to maintain price stability and support sustainable economic growth.

Factors Affecting Money Supply

Here are the factors affecting money supply.

-

Central Bank Policies:

Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States or the European Central Bank, have a significant influence on the money supply through their monetary policy decisions.

Open Market Operations: Central banks buy or sell government securities in the open market to adjust the level of reserves in the banking system. Purchases inject liquidity into the system, increasing the money supply, while sales reduce liquidity, decreasing the money supply.

Reserve Requirements: Central banks set reserve requirements, specifying the minimum amount of reserves that commercial banks must hold against their deposits. By changing reserve requirements, central banks can directly affect the ability of banks to create new money through lending.

Discount Rate: Central banks establish the discount rate, which is the interest rate at which commercial banks can borrow funds from the central bank.

By raising or lowering the discount rate, central banks can influence the cost of borrowing for banks and thereby impact their lending activities and the money supply.

-

Commercial Banking Activities:

Commercial banks play a crucial role in creating and controlling the money supply through their lending and deposit-taking activities.

Fractional Reserve Banking: Commercial banks operate on a fractional reserve system, where they are required to hold only a fraction of their deposits as reserves. This allows them to lend out the remainder of the deposits, effectively creating new money in the form of loans.

Credit Creation: When a bank issues a loan, it simultaneously creates new deposits in the borrower’s account, effectively increasing the money supply. As borrowers spend the newly created deposits, they enter the banking system, further increasing the money supply through the deposit multiplier effect.

-

Government Actions:

Government fiscal policy decisions, such as taxation, spending, and borrowing, can indirectly impact the money supply.

Government Spending: Increased government spending can inject funds into the economy, increasing the money supply as these funds circulate through the economy.

Taxation: Taxes reduce disposable income and the funds available for spending and saving, potentially decreasing the money supply by withdrawing funds from circulation.

Borrowing: When governments borrow funds from the private sector or central bank, they may increase the money supply if the borrowed funds are deposited in banks and subsequently lent out.

-

Economic Conditions:

Economic conditions, such as interest rates, inflation, and economic growth, can affect the demand for money and influence the money supply.

Interest Rates: Changes in interest rates can impact the demand for money by affecting the cost of borrowing and the opportunity cost of holding money versus other interest-bearing assets.

Inflation Expectations: Expectations of future inflation can influence the demand for money, as individuals may seek to hold more money to protect against the eroding purchasing power of their wealth.

Economic Growth: Economic expansion typically leads to increased demand for credit and investment, prompting banks to extend more loans and expand the money supply to meet the growing needs of businesses and consumers.

-

Global Factors:

Global economic and financial developments, such as exchange rates, capital flows, and international trade, can also impact the money supply.

Exchange Rates: Fluctuations in exchange rates can affect the demand for and supply of money by influencing trade flows, capital movements, and monetary policy decisions.

Capital Flows: Cross-border capital flows can impact domestic money supply dynamics by affecting the availability of funds for lending and investment, as well as influencing exchange rates and interest rates.

International Trade: Changes in international trade patterns and trade imbalances can influence the demand for money through their effects on exports, imports, and foreign exchange reserves.

By understanding these factors and their interrelationships, policymakers, economists, and investors can analyze changes in the money supply, anticipate their impact on the economy, and formulate appropriate responses to achieve macroeconomic objectives such as price stability, full employment, and sustainable economic growth.

Criticisms on Money Supply Measures

Here are the criticisms and controversies surrounding money supply measures in detail:

-

Accuracy and Reliability Issues:

One of the primary criticisms of money supply measures is related to their accuracy and reliability. Traditional measures of money supply, such as M1, M2, and M3, may not fully capture the complexity of modern financial systems.

In particular, these measures may fail to account for the rapid growth of non-bank financial intermediaries, such as money market mutual funds, hedge funds, and shadow banking entities, which play an increasingly significant role in money creation and credit provision.

Additionally, the proliferation of digital payment systems and cryptocurrencies has introduced new challenges for measuring and tracking money supply, as these forms of money may not be captured by traditional monetary aggregates.

-

Lack of Consensus on Definition and Measurement:

There is often a lack of consensus among economists and policymakers regarding the appropriate definition and measurement of money supply.

Different monetary aggregates may capture different aspects of the money supply, leading to inconsistencies in analysis and policy formulation.

For example, while some economists advocate for a narrow definition of money supply focusing on base money or high-powered money (M0), others argue for a broader definition that includes various forms of bank deposits and financial assets.

-

Endogeneity of Money Supply:

Critics argue that traditional measures of money supply fail to adequately account for the endogenous nature of money creation within the banking system.

In a fractional reserve banking system, commercial banks create money through the process of credit creation when they extend loans to borrowers. This process can significantly increase the effective money supply beyond the levels captured by traditional monetary aggregates.

As a result, changes in the money supply may not always be directly controlled or influenced by central bank policies, undermining the effectiveness of traditional monetary policy tools in controlling inflation and economic activity.

-

Role of Financial Innovation:

Financial innovation and technological advancements have introduced new forms of money and payment systems that challenge traditional measures of money supply.

Digital currencies, such as Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, operate outside the traditional banking system and may not be included in conventional measures of money supply.

Similarly, the emergence of peer-to-peer lending platforms, crowdfunding, and mobile payment services has blurred the distinction between traditional banking and non-bank financial activities, complicating efforts to measure and regulate the money supply.

-

Alternative Views on Monetary Policy:

Some economists and policymakers advocate for alternative approaches to monetary policy that focus on targeting interest rates or inflation directly, rather than controlling the money supply.

These proponents argue that targeting interest rates or inflation allows central banks to achieve their policy objectives more effectively by directly influencing borrowing costs, inflation expectations, and economic activity.

However, critics of this approach contend that it may lead to unintended consequences, such as asset price bubbles or financial instability, and limit the central bank’s ability to respond to changes in the financial system or economic conditions.

Addressing these criticisms and controversies surrounding money supply measures requires ongoing research, innovation, and collaboration among economists, policymakers, and financial institutions.

By adapting measurement techniques, improving data collection methods, and incorporating insights from new economic theories, stakeholders can enhance their understanding of the money supply and its implications for monetary policy and financial stability.

Determinants of the Money Supply

The money supply in an economy is influenced by various factors, known as determinants, which shape the availability of money and credit within the financial system. Let’s explore these determinants in detail:

-

Monetary Base (MB):

The monetary base, also known as high-powered money or the monetary base, refers to the total amount of currency in circulation (C) plus reserves held by commercial banks at the central bank (R).

Changes in the monetary base directly impact the money supply through the money multiplier effect. An increase in the monetary base, such as through central bank purchases of government securities, injects liquidity into the banking system, allowing banks to expand their lending and increase the money supply.

Conversely, a decrease in the monetary base reduces bank reserves, constraining their ability to lend and leading to a contraction in the money supply.

-

Reserve Requirements:

Reserve requirements refer to the percentage of deposits that banks are required to hold as reserves, either in the form of cash or as deposits with the central bank.

Changes in reserve requirements directly affect the amount of reserves banks must hold against their deposits. Lowering reserve requirements increases the excess reserves available for lending, leading to an expansion of the money supply. Conversely, raising reserve requirements reduces excess reserves, constraining bank lending and decreasing the money supply.

-

Central Bank Operations:

Central banks conduct various operations, such as open market operations, discount rate adjustments, and changes in the interest paid on reserves, to influence the money supply.

Open Market Operations: Central banks buy or sell government securities in the open market to adjust the level of reserves in the banking system. Purchases inject liquidity into the system, increasing the money supply, while sales reduce liquidity, decreasing the money supply.

Discount Rate: Central banks establish the discount rate, which is the interest rate at which commercial banks can borrow funds from the central bank.

By raising or lowering the discount rate, central banks can influence the cost of borrowing for banks and thereby impact their lending activities and the money supply.

Interest on Reserves: Central banks may pay interest on reserves held by commercial banks, encouraging banks to hold excess reserves rather than lending them out. By adjusting the interest rate paid on reserves, central banks can influence the level of excess reserves and the money supply.

-

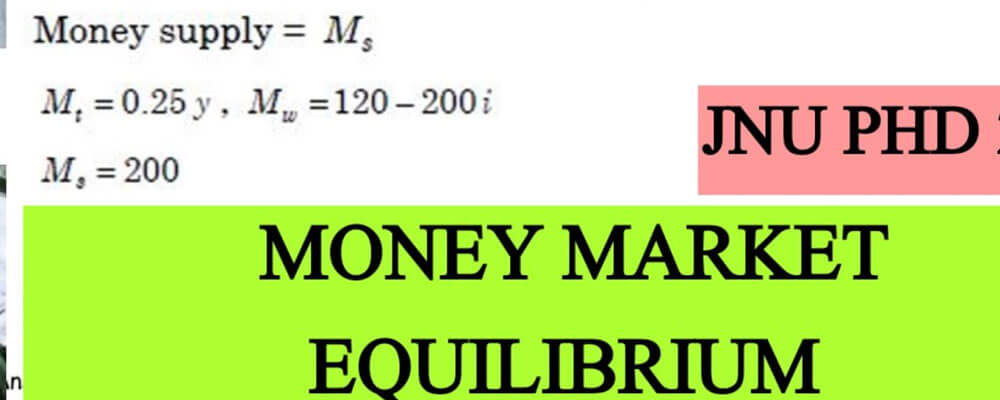

Demand for Money:

The demand for money, or liquidity preference, reflects individuals’ and businesses’ desire to hold money for transactional purposes, precautionary savings, and speculative motives.

Changes in the demand for money can influence the velocity of money, which measures the rate at which money circulates in the economy.

An increase in the demand for money, such as during the periods of economic uncertainty or financial instability, it may leads to a decrease in the velocity of money, reducing the effectiveness of monetary policy in influencing the money supply.

-

Economic Activity and Credit Demand:

Economic activity and credit demand play a crucial role in determining the money supply, as banks create money through the process of credit creation when they extend loans to borrowers.

During periods of economic expansion, increased business investment and consumer spending drive up credit demand, prompting banks to extend more loans and increase the money supply.

Conversely, during economic downturns, reduced credit demand leads to a contraction in bank lending and a decrease in the money supply.

-

Financial System Structure and Regulations:

The structure of the financial system, including the number and size of banks, the degree of competition, and the regulatory environment, influences the effectiveness of monetary policy in controlling the money supply.

Banking regulations, such as capital adequacy requirements, liquidity ratios, and restrictions on lending practices, shape banks’ ability to create money through the process of credit creation.

Changes in these regulations can impact the extent to which changes in the monetary base translate into changes in the broader money supply.

The determinants of the money supply encompass a wide range of factors, including the monetary base, reserve requirements, central bank operations, and demand for money, economic activity, and financial system structure.

By understanding these determinants and their interrelationships, policymakers and central banks can formulate effective monetary policy strategies to achieve their policy objectives, such as price stability, full employment, and sustainable economic growth.

How Money Supply Affects the Economy

The money supply plays a crucial role in shaping various aspects of economic activity, influencing inflation, interest rates, investment decisions, aggregate demand, and financial stability. Let’s explore in detail how changes in the money supply affect the economy:

-

Inflation:

One of the primary channels through which changes in the money supply impact the economy is through inflation.

An increase in the money supply, if not matched by a corresponding increase in goods and services, can lead to an excess of money relative to the available supply of goods, leading to inflationary pressures.

As individuals and businesses have more money to spend, they bid up prices for goods and services, causing inflation. Conversely, a decrease in the money supply, or a slowdown in its growth rate, can mitigate inflationary pressures or even lead to deflation if the reduction in money supply outpaces the decrease in economic output.

-

Interest Rates:

Changes in the money supply directly influence interest rates, which in turn affect borrowing and lending decisions, investment choices, and overall economic activity.

An increase in the money supply tends to lower interest rates as the abundance of money in the financial system reduces the cost of borrowing. Lower interest rates stimulate investment and consumption, leading to increased aggregate demand and economic growth.

Conversely, a decrease in the money supply can lead to higher interest rates as the scarcity of money increases the cost of borrowing. Higher interest rates can dampen investment and consumption, leading to a slowdown in economic activity.

-

Aggregate Demand and Economic Growth:

Changes in the money supply directly impact aggregate demand, which represents the total spending on goods and services in the economy.

An expansionary monetary policy that increases the money supply stimulates aggregate demand by reducing borrowing costs, encouraging businesses and consumers to increase spending and investment. This, in turn, boosts economic growth and employment.

Conversely, a contractionary monetary policy that reduces the money supply can dampen aggregate demand by raising borrowing costs, leading to lower spending, investment, and economic growth.

-

Asset Prices and Financial Markets:

Changes in the money supply can influence asset prices, including stocks, bonds, real estate, and commodities.

An increase in the money supply tends to drive up asset prices as investors seek higher returns in response to lower interest rates and increased liquidity. Rising asset prices can create wealth effects, boosting consumer confidence and spending.

Conversely, a decrease in the money supply can lead to lower asset prices as investors become more risk-averse in response to higher borrowing costs and reduced liquidity. Falling asset prices can dampen consumer sentiment and spending, leading to economic contraction.

-

Exchange Rates:

Changes in the money supply can impact currency exchange rates as investors adjust their expectations about interest rates, inflation, and economic growth.

An increase in the money supply, accompanied by lower interest rates, may lead to a depreciation of the domestic currency as investors seek higher returns abroad.

A weaker currency can boost exports and economic competitiveness but may also increase import prices and inflation.

Conversely, a decrease in the money supply, accompanied by higher interest rates, may lead to an appreciation of the domestic currency as investors flock to higher-yielding assets. A stronger currency can reduce export competitiveness but may lower import prices and inflation.

-

Financial Stability and Systemic Risk:

Changes in the money supply can impact financial stability by influencing the availability of credit, the level of leverage in the financial system, and the risk-taking behavior of financial institutions.

Excessive growth in the money supply, particularly when accompanied by lax lending standards and speculative behavior, can lead to asset bubbles, excessive leverage, and systemic risks in the financial system.

Conversely, a contraction in the money supply, or a sudden tightening of credit conditions, can trigger financial distress, credit crunches, and banking crises, jeopardizing the stability of the financial system and overall economic stability.

The effect of money supply on the economy is far-reaching and complex, influencing key macroeconomic variables such as inflation, interest rates, economic growth, asset prices, exchange rates, and financial stability.

Central banks and policymakers closely monitor changes in the money supply and adjust monetary policy to achieve their policy objectives, such as price stability, full employment, and sustainable economic growth.

What is Money Supply | Definition | Types | Components | Factors | Criticism | PDF Free Download |

Conclusion

Money supply serves as the lifeblood of modern economies, exerting a profound influence on economic activity, inflation, and interest rates. Understanding the components, factors, and implications of changes in the money supply is essential for policymakers, investors, and individuals navigating the complexities of the financial system.

By analyzing historical trends, embracing technological innovations, and addressing inherent challenges, societies can harness the power of money supply management to promote sustainable economic growth and financial stability.

See Also: What is Money | Functions of Money | Importance of Money