Aggregate Demand, often denoted as AD, is a fundamental concept in macroeconomics that represents the total quantity of goods and services demanded within an economy at a given price level and in a given time period. It reflects the combined demand from households, businesses, government, and net exports (exports minus imports).

Aggregate Demand is a cornerstone in macroeconomic analysis as it helps assess an economy’s performance, make policy decisions, and understand the factors driving economic fluctuations.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is Aggregate Demand | Different Definitions

Aggregate Demand (AD) is a central concept in macroeconomics, representing the total demand for goods and services within an economy at a specific price level and time. Various economists have provided definitions and insights into AD, reflecting different perspectives on this fundamental economic concept. Here are different definitions of Aggregate Demand by different authors:

- John Maynard Keynes defined Aggregate Demand as the total spending or expenditure on all goods and services in an economy at any given level of output.

- Paul Samuelson Aggregate Demand as the total demand in an economy, combining consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports.

- Milton Friedma viewed Aggregate Demand as the sum of total consumer spending, total investment spending, and government spending. He emphasized the significance of money supply in determining AD.

- James Tobin, an influential economist, defined Aggregate Demand as the total of desired spending on the economy’s total output. He stressed that AD should be aligned with the economy’s productive capacity to avoid inflation or recession.

- Ben Bernanke, described Aggregate Demand as the total demand for the economy’s goods and services, influenced by consumer spending, business investments, government purchases, and exports minus imports.

- According to Jean-Baptiste Say, as long as goods and services are produced, there will be sufficient demand to purchase them.

These diverse definitions reflect the multifaceted nature of Aggregate Demand and highlight its role as a fundamental component of macroeconomic analysis. While the core idea of AD as the total demand for goods and services remains constant, the specific components and emphases may vary among economists, depending on their economic theories and perspectives.

Importance of Aggregate Demand

- Economic Stabilization: An understanding of Aggregate Demand allows policymakers to stabilize the economy. By managing AD, governments can counteract fluctuations in economic activity, striving for steady growth and reducing the risk of recessions.

- Inflation Control: An excessive AD can lead to inflation, while insufficient AD can result in deflation or economic downturns. Knowledge of AD helps central banks make informed decisions regarding interest rates and money supply to manage inflation.

- Impact on Business Strategy: For firms, understanding AD is essential. Firms assess AD to determine product demand, production levels, and pricing strategies. It influences business investment decisions.

- Labor Market: AD has a direct bearing on employment levels. When AD is high, employers are more likely to hire, and when it’s low, layoffs may occur. Policymakers use AD information to address employment concerns.

- Government Spending: Governments allocate resources based on AD analysis. A deeper understanding helps in making informed choices about public spending, taxation, and fiscal policy to support economic growth.

- Investment Decisions: Investors and financial markets monitor AD indicators to make investment decisions. Movements in AD can impact financial markets and asset values.

- Global Trade: AD includes net exports, which affect a nation’s trade balance. Understanding AD is crucial for countries engaged in international trade.

- Policy Formulation: Governments, central banks, and policymakers rely on AD to craft economic policies. They use it to influence economic parameters like inflation, unemployment, and economic growth.

- Business Cycles: AD plays a pivotal role in the business cycle. It helps explain the phases of expansion, peak, recession, and recovery within an economy. Monitoring AD can assist in anticipating business cycle fluctuations.

- Economic Well-Being: Ultimately, understanding AD is essential for enhancing overall economic well-being. It forms the basis for achieving higher standards of living, reducing poverty, and improving the quality of life for citizens.

Understanding Aggregate Demand is critical for policymakers, businesses, and individuals to navigate the complexities of the economy. It guides decisions on economic stability, monetary and fiscal policies, business strategies, employment, investment, trade, and overall prosperity.

Components of Aggregate Demand

Aggregate Demand (AD) is a critical concept in macroeconomics, representing the total demand for goods and services within an economy. It is composed of various components that together determine the level of economic activity in a country. Here are the components of Aggregate Demand in detail:

-

Consumer Spending (C):

Consumer spending is the largest component of Aggregate Demand. It includes expenditures by households on goods and services such as groceries, clothing, housing, healthcare, and leisure activities.

Factors influencing consumer spending include disposable income, consumer confidence, and interest rates. When consumers feel optimistic about their financial situation and the overall economy, they tend to spend more.

-

Business Investment (I):

Business investment refers to spending by firms on capital goods, such as machinery, equipment, and buildings. It also includes research and development activities.

Business investment is influenced by factors like interest rates, business confidence, and expectations of future profitability. When businesses expect higher future demand, they are more likely to invest.

-

Government Spending (G):

Government spending comprises all government expenditures on goods and services, such as defense, education, infrastructure, and public administration. It also includes transfer payments like Social Security and unemployment benefits.

Government spending can be influenced by fiscal policies set by the government, such as changes in tax rates and government budget decisions.

-

Net Exports (X – M):

Net exports represent the difference between a country’s exports (X) and imports (M). If exports exceed imports, it contributes positively to AD; if imports are greater, it has a negative impact.

Factors affecting net exports include exchange rates, trade policies, and the economic conditions of trading partners.

-

Net Exports (X – M):

Net exports represent the difference between a country’s exports (X) and imports (M). If exports exceed imports, it contributes positively to AD; if imports are greater, it has a negative impact.

Factors affecting net exports include exchange rates, trade policies, and the economic conditions of trading partners.

-

Net Exports (X – M):

Net exports represent the difference between a country’s exports (X) and imports (M). If exports exceed imports, it contributes positively to AD; if imports are greater, it has a negative impact.

Factors affecting net exports include exchange rates, trade policies, and the economic conditions of trading partners.

-

Net Exports (X – M):

Net exports represent the difference between a country’s exports (X) and imports (M). If exports exceed imports, it contributes positively to AD; if imports are greater, it has a negative impact.

Factors affecting net exports include exchange rates, trade policies, and the economic conditions of trading partners.

-

Net Exports (X – M):

Net exports represent the difference between a country’s exports (X) and imports (M). If exports exceed imports, it contributes positively to AD; if imports are greater, it has a negative impact.

Factors affecting net exports include exchange rates, trade policies, and the economic conditions of trading partners.

Aggregate Demand is the total of these components, and it plays a pivotal role in determining a nation’s overall economic output and growth. Economists use the AD framework to analyze and forecast economic conditions and to formulate policies that can stabilize and stimulate an economy.

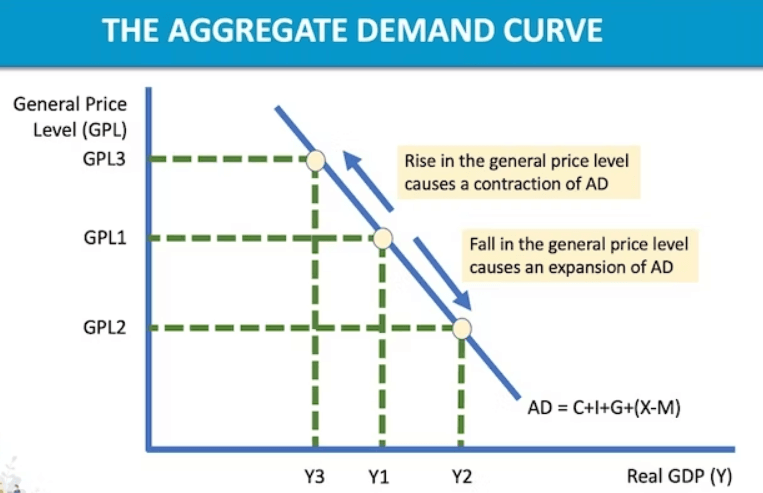

The Aggregate Demand Curve

The Aggregate Demand (AD) curve is a graphical representation of the total demand for goods and services within an economy at different price levels. It shows the relationship between the overall price level and the quantity of real GDP (Gross Domestic Product) demanded by households, businesses, government, and foreign buyers. Here’s a detailed explanation of the Aggregate Demand curve:

Components of the Aggregate Demand Curve:

The AD curve is typically downward-sloping, meaning that as the price level increases, the quantity of real GDP demanded decreases. This relationship is driven by the following components:

- Consumer Spending (C): As the price level rises, consumers’ purchasing power decreases, leading to a reduction in their spending. Higher prices reduce the real value of income, making goods and services more expensive. Consequently, consumers buy less.

- Investment Spending (I): Higher prices can negatively impact business investment. Firms may delay or reduce capital investments in machinery, equipment, and facilities, which results in decreased demand for capital goods.

- Government Spending (G): Government spending is generally independent of price levels. However, it can influence the AD curve if fiscal policies change. For instance, an increase in government spending can shift the AD curve to the right, increasing total demand.

- Net Exports (X – M): When prices rise domestically relative to other countries, exports may decline while imports increase. This reduces net exports and negatively affects the AD curve. Conversely, a weaker domestic currency can boost exports and help shift the AD curve to the right.

Shifts in the Aggregate Demand Curve:

The AD curve can shift to the right or left, representing changes in total demand caused by factors other than price levels. These shifts include:

- Changes in Consumer Confidence: Improved consumer confidence can lead to higher consumer spending, shifting the AD curve to the right.

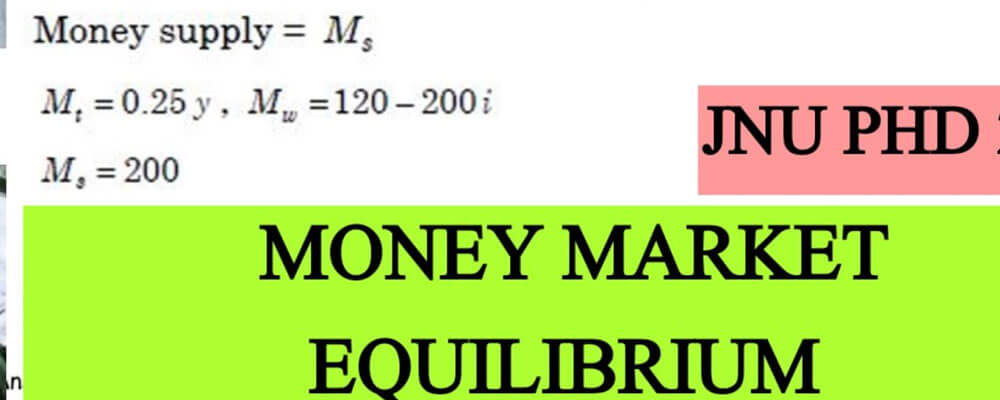

- Monetary Policy: Central banks can influence interest rates and money supply. Lower interest rates stimulate investment and consumer spending, shifting AD to the right.

- Fiscal Policy: Government policies, such as tax cuts or increased public spending, can impact the AD curve. Expansionary fiscal policies can boost AD, while contractionary policies can reduce it.

- Exchange Rates: Changes in exchange rates can influence net exports. A weaker domestic currency can increase exports and shift the AD curve to the right.

Economic Equilibrium:

The point where the AD curve intersects the Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS) curve represents the equilibrium in the economy. This point indicates the combination of price levels and real GDP where total demand matches total supply. Economists use this equilibrium to analyze inflationary and recessionary gaps.

The Aggregate Demand curve is a fundamental tool in macroeconomics, helping us understand the relationship between the price level and the quantity of goods and services demanded by various economic agents. Shifts in the AD curve reflect changes in overall demand influenced by various economic factors.

Criticisms and Controversies

Critics and controversies surrounding the concept of Aggregate Demand (AD) in macroeconomics have given rise to various debates and discussions. Here are some of the key criticisms and controversies related to AD:

-

Assumptions of Rational Expectations:

Critics argue that the AD model relies on the assumption of rational expectations, which means that individuals and firms form their expectations about future economic conditions based on all available information. In reality, people’s expectations can be influenced by various factors, and they may not always make perfectly rational decisions. Critics contend that this assumption doesn’t accurately reflect human behavior.

-

Short-Term Focus:

The AD model primarily focuses on short-term economic fluctuations. It assumes that the economy will eventually reach full-employment equilibrium. Critics argue that this view neglects long-term economic issues, such as economic growth, income distribution, and structural changes in the economy.

-

Aggregate Variables Oversimplify:

Critics claim that the use of aggregate variables in AD models oversimplifies the complexities of individual and firm behavior. The model assumes homogeneity within different economic sectors, ignoring variations among different industries and regions.

-

Assumption of Fixed Prices:

The AD model typically assumes that prices and wages are fixed in the short run. Critics argue that this assumption may not always hold in reality, and that prices and wages can adjust in response to changes in aggregate demand. This criticism challenges the concept of the Keynesian short-run AS curve.

-

Inflation Expectations:

Critics point out that the AD model sometimes doesn’t adequately consider inflation expectations. In an environment with rising prices, individuals and businesses may expect higher inflation rates in the future, leading to adjustments in their economic behavior. Failing to account for these inflation expectations can be a limitation of AD models.

-

External Shocks:

The AD model assumes that changes in the price level solely result from fluctuations in aggregate demand. However, external shocks, such as oil price spikes, natural disasters, or geopolitical events, can significantly impact an economy’s price level. Critics contend that the AD model doesn’t adequately address these external factors.

-

Real-World Complexity:

Some critics argue that the AD model doesn’t capture the full complexity of the real world, where various economic and non-economic factors influence economic behavior. While AD provides a useful framework for analysis, it may not encompass all the intricacies of economic decision-making.

-

Monetary Policy Effectiveness:

Controversies also arise regarding the effectiveness of monetary policy. The AD model suggests that central banks can influence aggregate demand through interest rate adjustments. However, the extent to which changes in monetary policy translate into actual changes in spending and demand is debated.

-

Fiscal Policy and Crowding Out:

Fiscal policy changes, such as government spending and taxation, can influence aggregate demand. Critics question the potential for “crowding out” private sector investment, meaning that increased government spending may reduce private investment due to higher interest rates.

-

Cyclical Unemployment:

Critics argue that the AD model doesn’t sufficiently address structural or long-term unemployment issues. It primarily focuses on short-term cyclical unemployment caused by fluctuations in AD, potentially neglecting the need for labor market and structural reforms.

It’s essential to note that these criticisms and controversies don’t negate the value of the Aggregate Demand model but rather emphasize the need for a comprehensive understanding of its assumptions, limitations, and real-world complexities when analyzing and making policy decisions about an economy.

Aggregate Demand and the Business Cycle

Aggregate Demand (AD) plays a crucial role in understanding the business cycle. The business cycle refers to the fluctuations in economic activity characterized by periods of economic expansion and contraction. Here’s an in-depth explanation of the relationship between Aggregate Demand and the business cycle:

-

Business Cycle Phases:

The business cycle consists of four main phases:

Expansion: This is a period of economic growth characterized by rising output, employment, and income. Consumers and businesses are confident, leading to increased spending and investment. In the context of AD, the AD curve typically shifts to the right, reflecting increased spending and rising aggregate demand.

Peak: The peak marks the highest point of economic activity during an expansion. It’s a phase of maximum output and employment, but it can also lead to inflationary pressures. At this stage, AD may approach or even exceed the economy’s full-employment level.

Contraction: This phase, also known as a recession, is characterized by declining economic activity, falling output, employment, and income. It’s often caused by a decline in AD. During a contraction, the AD curve shifts to the left as consumer spending and business investments decline.

Trough: The trough is the lowest point of the business cycle, representing the end of the contraction. At this stage, AD may be at its lowest, and the economy is operating below its potential. Unemployment is typically high, and businesses may cut production.

-

AD and Economic Fluctuations:

Components of AD: Aggregate Demand is composed of four main components: consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G), and net exports (NX). The fluctuations in these components can drive changes in AD and influence the business cycle.

Consumer and Business Confidence: The business cycle is heavily influenced by consumer and business confidence. When consumers and businesses feel optimistic about the future, they are more likely to spend and invest, boosting AD during an expansion. Conversely, during a contraction, declining confidence can lead to reduced spending and investment, further contributing to the downturn.

Monetary and Fiscal Policy: Central banks and governments often use monetary and fiscal policy tools to influence AD. For example, during a recession, central banks may lower interest rates to stimulate borrowing and spending. Governments may increase public spending to boost AD during economic downturns. Conversely, during periods of overheating and inflation, policy authorities may employ measures to cool down AD.

-

Role of AD in Policy Making:

Policymakers closely monitor AD as they aim to stabilize the economy. They use various tools to influence AD. For example, central banks use interest rates to impact borrowing costs and, consequently, consumption and investment. Fiscal policy authorities can adjust government spending and taxation to influence the components of AD.

Understanding the position of the economy within the business cycle is crucial for policymakers. During periods of expansion, they may aim to prevent excessive inflation, while during contractions, they focus on stimulating economic activity and reducing unemployment.

-

Challenges and Limitations:

AD is a valuable concept for understanding economic fluctuations, but it has limitations. It doesn’t always capture the complexity of economic dynamics. For instance, it may not fully account for structural issues in the labor market or supply-side shocks.

Economic data can be subject to revisions, making it challenging to precisely identify the turning points in the business cycle. Additionally, economic policies may have lags in their effects, and policymakers may need to anticipate changes in AD.

Aggregate Demand plays a pivotal role in understanding the business cycle. The components of AD and their fluctuations influence economic activity and are essential considerations for policymakers seeking to stabilize the economy during various phases of the business cycle.

Policy Implications

Governments use Aggregate Demand (AD) as a vital tool to achieve economic goals and stabilize their economies. By influencing AD, policymakers aim to achieve various macroeconomic objectives. Here’s a detailed explanation of how governments use AD to meet their economic goals:

-

Full Employment:

One of the primary economic goals is to achieve and maintain full employment, where everyone willing and able to work has a job.

Governments can stimulate employment by increasing AD. For example, they can boost public infrastructure projects, leading to increased government spending (G) and job creation.

By reducing interest rates through monetary policy, governments can encourage borrowing and investment by businesses, leading to job creation.

-

Price Stability:

Price stability is another critical economic objective, and governments aim to keep inflation in check.

A high level of AD can lead to demand-pull inflation. To control this, governments can use monetary policy to increase interest rates, which reduces borrowing and spending. By reducing AD, they mitigate inflationary pressures.

-

Economic Growth:

Governments strive for sustainable economic growth to increase a nation’s standard of living.

Expansionary fiscal and monetary policies can boost AD, leading to higher economic growth. Lower interest rates and increased government spending can stimulate consumer and business spending, leading to increased output and GDP growth.

-

Income Distribution:

Achieving a fair income distribution is another economic objective. Governments can use AD to address income inequality.

By focusing on government spending programs that target lower-income individuals and families, policymakers can enhance AD for these groups, boosting their disposable income.

-

Balance of Payments:

Governments also aim to maintain a balance in their nation’s international trade. A large trade deficit can be a concern.

Adjusting the value of a nation’s currency can influence the trade balance. For example, a weaker currency can make exports more attractive, boosting net exports (NX) and increasing AD.

-

Exchange Rate Stability:

Exchange rate stability is vital for a nation’s economic security and international trade.

Governments can influence exchange rates to stabilize them. For example, they may engage in foreign exchange interventions to prevent drastic currency fluctuations, which can impact AD through its effect on NX.

-

Environmental Sustainability:

In recent years, environmental sustainability has become an essential goal. Governments use AD to promote environmentally friendly policies.

Tax incentives, subsidies, and government spending on green initiatives can encourage eco-friendly consumption and production, influencing AD while supporting sustainability.

-

Managing Economic Shocks:

Governments also use AD to counteract economic shocks. In response to recessions or economic crises, they may implement expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to boost AD and stabilize the economy.

-

Counter-Cyclical Policies:

To prevent overheating during periods of economic expansion, governments may employ contractionary policies, such as raising interest rates or reducing government spending. These measures help prevent inflation by reducing AD.

Governments utilize various fiscal and monetary policies to influence AD, aiming to achieve their economic goals and stabilize their economies. By skillfully managing AD, policymakers can address unemployment, inflation, economic growth, income distribution, and other key objectives in their efforts to create a more stable and prosperous economy.

Examples of Aggregate Demand

Real-world examples of aggregate demand (AD) and its effects can be observed in various economic situations. Here are some detailed examples of how AD works in practice:

-

Government Stimulus during the 2008 Financial Crisis:

The 2008 financial crisis led to a significant decrease in consumer and business spending. To counteract the recession, governments in many countries implemented expansionary fiscal policies.

The U.S. government, for instance, initiated the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which involved substantial public spending on infrastructure projects, unemployment benefits, and tax cuts. These measures increased aggregate demand and helped the economy recover.

-

Monetary Policy and the Housing Market:

Central banks use monetary policy to influence AD. For example, when central banks reduce interest rates, it becomes cheaper to borrow money, which can stimulate consumer spending, housing demand, and business investment.

During the global financial crisis of 2008, central banks worldwide lowered interest rates to near zero. This encouraged borrowing, especially in the housing market, where lower mortgage rates spurred higher demand for homes.

-

Consumer Confidence and Spending Habits:

The level of consumer confidence in the economy can significantly affect AD. When consumers are optimistic about the future, they tend to spend more, which increases AD.

For example, during periods of strong economic growth, consumers often feel more secure about their finances, leading to increased consumption and higher AD.

-

Effect of Exchange Rates on Export and Import Demand:

Exchange rates influence a country’s net exports (exports minus imports), which is a component of AD. A weaker domestic currency can make a country’s goods more competitive in international markets, boosting exports.

For example, a depreciation of the Japanese yen against the U.S. dollar increases the competitiveness of Japanese exports, leading to higher demand for Japanese products overseas.

-

Government Infrastructure Investment:

Government spending on infrastructure projects, such as road construction or building public transportation systems can have a significant impact on AD.

For instance, the “New Deal” programs in the U.S. during the Great Depression involved large-scale infrastructure investments that boosted AD and helped the country recover from the economic downturn.

-

Seasonal Demand Fluctuations:

AD often experiences seasonal fluctuations. During holidays and shopping seasons, consumer spending typically rises, reflecting increased demand for goods and services.

Retailers prepare for this by hiring more workers and stocking extra inventory, affecting both short-term and long-term AD.

These real-world examples illustrate how aggregate demand responds to various economic and policy influences, affecting economic growth, inflation, employment, and overall economic stability. Policymakers and economists closely monitor AD to make informed decisions and implement appropriate policies to achieve desired economic outcomes.

Aggregate Demand | Importance | Components | Curve | Limitations | PDF Free Download |

Conclusion:

Understanding the concept of aggregate demand (AD) is of paramount significance in the field of macroeconomics. Aggregate demand serves as a foundational framework that encapsulates the overall demand for goods and services within an economy. It plays a central role in shaping economic policies and assessing the overall health of an economy.

Aggregate demand is a cornerstone concept in macroeconomics. It offers a lens through which to view an economy’s performance, and it guides policymakers in their efforts to maintain economic stability and promote growth. A nuanced understanding of AD is essential for anyone seeking to comprehend the complex interplay of factors that shape an economy’s trajectory and its ability to achieve macroeconomic objectives.

See Also: Aggregate Demand and Supply | The Classical View Explained