In the realm of economics, market structures vary widely, each exhibiting unique characteristics that impact competition, pricing, and overall market behavior.

Oligopoly, one such market structure, stands out as a complex and intriguing arrangement that plays a pivotal role in shaping modern economies.

In this post, we will see what is oligopoly, examining its definition, distinctive traits, and its profound significance in contemporary economic landscapes.

See Also: Economics Notes in PDF

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is Oligopoly | Different Definitions

Oligopoly is a market structure characterized by a small number of large firms dominating the industry. These firms have the power to influence the market, often resulting in intense competition and strategic interactions. Various economists and scholars have provided different definitions of oligopoly:

- Alfred E. Kahn defines oligopoly as a market structure where “the number of firms is small enough that strategic, rather than purely competitive, considerations affect decision making.”

- Edward Chamberlin describes oligopoly as a situation where “a few firms dominate the market for a particular product or group of products.”

- Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus in their widely used textbook “Economics,” they define oligopoly as “a market situation in which there are very few sellers. That is, each seller is aware of the pricing and marketing decisions of the others.”

- According to Chamberlin, “Oligopoly refers to the market situation in which there are few firms, each firm being large enough to affect significantly the total market output or total sales, but not so large as to dominate the market.”

- Hal R. Varian: Varian, a microeconomics expert, defines oligopoly as “a market in which a small number of firms compete.”

Oligopoly is a market structure where a limited number of firms dominate a particular industry. These firms typically have substantial market power and can influence prices and market outcomes. Oligopolistic markets often involve strategic decision-making, such as pricing, advertising, and product differentiation, as firms are interdependent and must consider the reactions of their competitors.

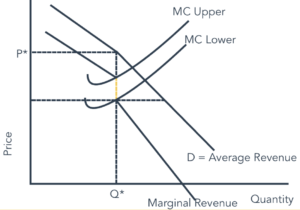

Graph of Oligopoly

Graphically representing an oligopoly market can help illustrate the behavior of firms in such a market structure. This graphical representation highlights the complexities and challenges faced by firms in oligopoly markets.

The kinked demand curve model explains price rigidity, while the prisoner’s dilemma illustrates the difficulty of achieving cooperation among self-interested firms. Understanding these concepts can provide valuable insights into the behavior of firms in oligopolistic industries.

Characteristics of Oligopolistic Markets

Oligopolistic markets are characterized by several distinctive features that set them apart from other market structures. These characteristics define the behavior of firms within these markets and contribute to their unique dynamics.

See Also: Price Discrimination in Economics | Types | Benefits | Criticisms | Examples | Strategies

-

Few Dominant Firms

Oligopolistic markets are characterized by a small number of dominant firms that account for a significant portion of total industry output or sales.

Typically, there are only a handful of major players in the market, often competing fiercely for market share. These firms have substantial influence over market conditions.

-

Interdependence

One of the most defining characteristics of oligopolistic markets is the interdependence of firms. Each firm’s decisions regarding pricing, production levels, product innovation, and marketing strategies significantly impact the decisions of its competitors. Firms must consider how their rivals will react to their actions, leading to strategic decision-making.

-

Barriers to Entry

Oligopolistic markets often feature high barriers to entry, which discourage new firms from entering and competing. These barriers can manifest in various ways, such as:

Economies of Scale: Existing firms may benefit from economies of scale, meaning they can produce goods or services at lower average costs as they expand. New entrants struggle to achieve the same cost efficiency.

Capital Requirements: Industries dominated by oligopolies may require substantial capital investments in machinery, technology, research and development, and infrastructure. New entrants may lack the necessary resources.

Product Differentiation: Many oligopolistic markets involve differentiated products, where firms invest heavily in branding, marketing, and product development. New entrants face challenges in establishing brand recognition and competing with established offerings.

Access to Distribution Channels: Oligopolistic firms may control essential distribution channels or have exclusive agreements with distributors. This limits the ability of new entrants to reach customers effectively.

-

Price Rigidity

Oligopolistic markets often exhibit price rigidity, meaning that prices remain relatively stable over time, even in the face of changes in demand or costs. Firms are hesitant to engage in price competition, as they are aware that aggressive price cuts could trigger retaliatory responses from competitors.

Instead, they may compete through non-price strategies such as advertising, product differentiation, or quality improvements.

-

Non-Price Competition

Due to the challenges associated with price competition, oligopolistic firms frequently engage in non-price competition. This includes efforts to differentiate their products through branding, marketing campaigns, innovation, customer service, and product quality. Firms aim to create brand loyalty and customer preferences to maintain or expand their market share.

-

Strategic Behavior

Firms in oligopolistic markets engage in strategic behavior, carefully considering their competitors’ responses to various decisions. This strategic thinking extends to pricing, advertising, product launches, and capacity expansion. Game theory often provides a framework for analyzing and predicting the outcomes of strategic interactions among oligopolists.

-

Collusion and Tacit Cooperation

Collusion, whether explicit or tacit, is common in oligopolistic markets. Colluding firms may coordinate their actions to manipulate prices, output levels, or market behavior to their advantage. Tacit cooperation involves firms indirectly coordinating their behavior without formal agreements, often leading to stable prices and reduced competition.

-

Product Homogeneity or Differentiation

Oligopolistic markets can feature either homogeneous products, where products are identical among firms, or differentiated products, where each firm offers a slightly distinct product. Homogeneous product oligopolies often result in intense price competition, while differentiated product oligopolies rely on product features and branding to compete.

-

Kinked Demand Curve

The kinked demand curve model is a theoretical concept in oligopoly. It suggests that firms face a demand curve with an elastic segment above the current price and an inelastic segment below it. As a result, firms may maintain existing prices to avoid potential adverse effects of price changes.

-

Advertising and Marketing

Oligopolistic firms invest significantly in advertising and marketing campaigns to build brand loyalty and differentiate their products. Advertising can be a critical tool for influencing consumer preferences and increasing market share.

These characteristics collectively shape the behavior of firms within oligopolistic markets, leading to complex interactions, strategic decision-making, and a focus on both price and non-price competition.

Importance of Oligopoly in Modern Economies

Understanding the significance of oligopoly in contemporary economies is pivotal. Oligopolistic markets are pervasive and shape a multitude of industries, influencing everything from consumer choices to government policies. Here are some key reasons why oligopoly matters:

- Market Concentration: Oligopolistic markets are characterized by a small number of dominant firms. These firms often control a substantial share of the market, which means their actions can have a substantial impact on the overall economy. For example, in the telecommunications industry, a few major companies control the majority of the market share, and their pricing decisions affect millions of consumers.

- Innovation and Competition: Oligopolies often compete vigorously in terms of product innovation and development. The competition for market share can drive firms to invest heavily in research and development, leading to technological advancements and the introduction of new products. For instance, in the smartphone industry, major players like Apple and Samsung constantly introduce new features and models to outdo each other.

- Price Stability: Oligopolistic markets tend to exhibit greater price stability compared to perfect competition. While firms in oligopolies have the power to set prices to some extent, they are also aware that aggressive price changes can trigger price wars or retaliation from competitors. This encourages them to maintain relatively stable prices over time, which can be beneficial for consumers and businesses.

- Economies of Scale: Oligopolistic firms often operate on a large scale, benefiting from economies of scale. This means they can produce goods or services more efficiently and at lower average costs. As a result, consumers may enjoy lower prices for certain products and services compared to a scenario with numerous small firms.

- Job Creation: Oligopolies are major employers, contributing significantly to job creation and economic growth. Large firms in sectors like automotive manufacturing or aerospace engineering employ a substantial workforce, offering stable employment opportunities and contributing to the overall economic well-being of a region.

- Tax Revenue: Oligopolistic firms generate substantial revenue, which translates into higher tax payments to governments. This revenue can be used to fund public services, infrastructure projects, and social welfare programs, benefiting society as a whole.

- Global Competition: Oligopolies often compete on a global scale, which can enhance a country’s competitiveness in the international market. When firms based in a particular country are major players in an oligopolistic industry, it can boost the nation’s trade balance and overall economic strength.

- Research and Development (R&D): Oligopolistic firms invest heavily in R&D to maintain a competitive edge. This investment not only fuels technological progress but also creates high-skill jobs in research, engineering, and design.

- Consumer Choice: While oligopolies may limit the number of competitors in a market, they often offer a wide range of products and services within their own portfolios. This diversity can provide consumers with various choices and options, even within the limited competitive landscape.

- Regulation and Oversight: Oligopolistic markets often attract regulatory scrutiny to ensure fair competition and protect consumer interests. Regulatory agencies monitor pricing practices, mergers, and anticompetitive behavior, helping to maintain a balance between market power and consumer welfare.

Oligopoly’s role in modern economies is complex. While it can lead to concentrated market power and potential disadvantages, it also drives innovation, job creation, and economic growth. Effective regulation and competition policy are essential to harness the benefits of oligopolistic markets while mitigating their potential drawbacks.

Different Types of Oligopolies

Oligopolistic markets can be categorized into different types based on the nature of competition and the strategic behavior of firms. These classifications offer insights into how firms within an oligopoly interact. The primary types of oligopolies include:

-

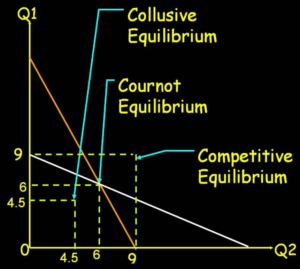

Collusive Oligopoly (Cartel):

In a collusive oligopoly, firms explicitly cooperate with one another to limit competition and maximize joint profits. This cooperation often takes the form of a cartel, where firms agree on pricing, production levels, and market sharing.

Cartels can lead to price fixing, output quotas, and market allocation agreements among firms. These agreements are usually illegal due to their anticompetitive nature.

Examples: The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a famous example of a collusive oligopoly in the oil industry. OPEC member countries cooperate to control oil production levels and stabilize prices.

-

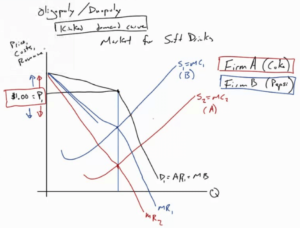

Non-Collusive Oligopoly (Non-Cooperative Oligopoly):

In a non-collusive oligopoly, firms do not engage in explicit cooperation but still recognize their interdependence. Each firm makes decisions independently based on its expectations of how competitors will react.

Firms in non-collusive oligopolies typically engage in competitive pricing, advertising, and product differentiation strategies to gain a competitive edge.

Examples: The soft drink industry is a non-collusive oligopoly where companies like Coca-Cola and PepsiCo compete aggressively in advertising, pricing, and product innovation.

-

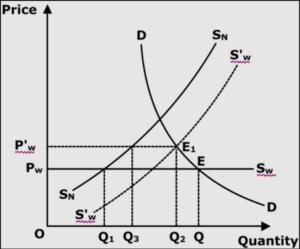

Price Leadership Oligopoly

Price leadership occurs when one dominant firm in the industry, often the largest or most influential, sets the price, and other firms follow suit without explicit coordination.

The price leader typically has stable market share and cost advantages that allow it to set prices. Other firms accept this price as a benchmark to avoid price wars.

Examples: The airline industry has seen examples of price leadership, where a major carrier sets fares, and smaller competitors adjust their prices accordingly.

-

Kinked Demand Curve Oligopoly:

In this model, firms assume that rivals will match price decreases but not price increases. As a result, the demand curve facing each firm has a kink at the current price level.

This model explains why prices in oligopolistic markets tend to be sticky and unresponsive to cost changes, as firms fear losing market share.

Examples: The smartphone industry is a classic example of a kinked demand curve oligopoly, where competitors closely monitor each other’s pricing moves.

-

Stackelberg Oligopoly:

Definition: In a Stackelberg oligopoly, there is a clear leader and follower among firms. The leader makes its strategic choice first, taking into account how the follower will respond.

Characteristics: The leader has a “first-mover advantage” and can set prices or quantities before the follower enters the market.

Examples: The video game console industry has seen examples of Stackelberg competition, where one company (e.g., Sony or Microsoft) launches a new console, and competitors follow with their own offerings.

-

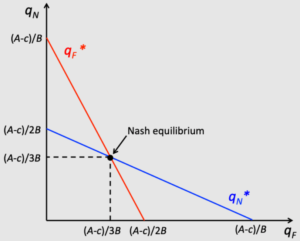

Cournot Oligopoly:

In a Cournot oligopoly, firms simultaneously decide how much output to produce. They consider how their rivals will react but do not set prices directly.

Firms adjust their production quantities to maximize profits given their expectations of rivals’ production levels. Cournot competition often results in intermediate levels of output.

Examples: The natural gas industry, where firms extract and sell gas based on production decisions, is a real-world example of Cournot competition.

These different types of oligopolies reflect the diverse ways in which firms interact and compete within concentrated markets. Understanding the specific characteristics of each type is crucial for analyzing market behavior and outcomes in oligopolistic industries.

Theories and Models of Oligopoly

Oligopoly models and theories provide frameworks for understanding the behavior and outcomes in markets characterized by a small number of interdependent firms. Here are some key oligopoly models and theories explained in detail:

-

Cournot Model

The Cournot model, developed by French economist Augustin Cournot in 1838, is one of the earliest formal models of oligopoly. It assumes that firms compete by simultaneously choosing their output quantities, taking their rivals’ quantities as given.

Key Assumptions:

- Firms are price-takers, meaning they do not set prices directly.

- Firms have perfect information about the market and their competitors.

- Firms have identical production costs.

In equilibrium, firms’ quantities are such that they maximize their profits given their rivals’ quantities. The Cournot equilibrium typically results in intermediate levels of production, falling between monopoly and perfect competition.

-

Stackelberg Model:

The Stackelberg model, developed by German economist Heinrich Stackelberg in 1934, extends the Cournot model by introducing the concept of leadership. It assumes that one firm (the leader) sets its quantity before other firms (the followers) make their decisions.

Key Assumptions:

- The leader is the first mover and has a competitive advantage.

- The leader can anticipate how followers will react to its output choice.

- Follower firms act as price-takers.

The Stackelberg leader produces a larger quantity than in Cournot competition, while followers produce less. The leader earns higher profits than in Cournot competition, and the followers earn lower profits.

-

Bertrand Model:

The Bertrand model, named after French economist Joseph Bertrand, focuses on price competition rather than quantity competition. Firms simultaneously choose the prices for their products, aiming to maximize their profits.

Key Assumptions:

- Firms have identical costs of production.

- Consumers always choose the lowest-priced product.

- Firms can adjust prices quickly.

In equilibrium, prices are driven down to marginal cost, resembling perfect competition. The Bertrand model highlights the importance of product differentiation, cost differences, or capacity constraints to prevent price undercutting.

-

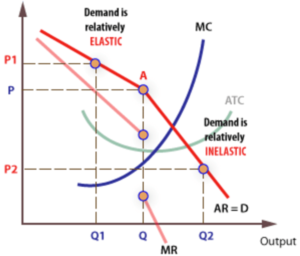

Kinked Demand Curve Model:

The kinked demand curve model suggests that firms in an oligopoly face a demand curve with an elastic segment (above the current price) and an inelastic segment (below the current price). The model explains price stickiness and the reluctance of firms to change prices.

Key Assumptions:

- Rival firms match price cuts but not price increases.

- Firms assume that competitors will maintain their prices.

Prices tend to remain stable, even in the face of cost changes. This model helps explain the observed price rigidity in many oligopolistic markets.

-

Sweezy Model (Kinked Demand Curve with Sticky Prices):

The Sweezy model extends the kinked demand curve model by incorporating the idea that prices are “sticky” or slow to adjust. Firms assume that their rivals will not match price reductions but will match price increases.

Key Assumptions:

- Firms have some degree of market power.

- Price changes are costly or difficult.

Prices remain stable within the kink of the demand curve. Firms have an incentive to maintain their prices rather than engage in price wars.

-

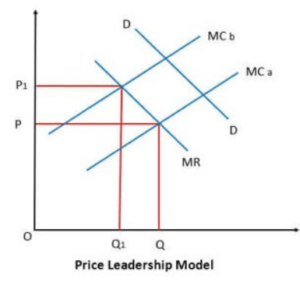

Price Leadership Model:

In the price leadership model, one dominant firm in the industry sets the price, and other firms passively follow suit without explicit coordination. The dominant firm’s price is seen as a signal for the market.

Key Assumptions:

- One firm is recognized as the leader.

- Follower firms accept the leader’s price as a benchmark.

The dominant firm can influence market prices, and followers adjust their prices accordingly. Price leadership is often observed in industries with a clear market leader.

These oligopoly models and theories provide valuable insights into the pricing and output decisions of firms in concentrated markets. Understanding these models helps economists and analysts analyze market behavior and predict outcomes in oligopolistic industries.

Concentration Ratios and Market Structure

Analyzing market concentration is essential in assessing the degree of competition within an oligopoly. Concentration ratios, such as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and the Four-Firm Concentration Ratio, offer valuable insights into market structure.

These ratios measure the market share held by a specific number of the largest firms within an industry.

- Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI): The HHI quantifies market concentration by summing the squares of the market shares of all firms in the market. The higher the HHI, the more concentrated the market. Regulators often use this index to assess the potential anticompetitive effects of mergers and acquisitions.

- Four-Firm Concentration Ratio: This ratio, as the name suggests, calculates the combined market share of the four largest firms in an industry. A high concentration ratio indicates that a small number of firms dominate the market.

Understanding market concentration helps policymakers and economists assess the level of competition and the potential for anticompetitive behavior within oligopolistic industries.

Collusion and Price Fixing

Collusion, whether explicit or tacit, is a defining feature of certain oligopolistic markets. It involves firms cooperating to manipulate prices, output levels, or market behavior to their advantage. Understanding the types of collusion and their implications is crucial in studying oligopoly.

- Tacit Collusion: Tacit collusion occurs when firms in an oligopoly coordinate their actions without explicit agreements. This form of collusion often results in stable prices and reduced competition. Firms monitor each other’s behavior and adjust their strategies accordingly to maintain a delicate balance.

- Explicit Collusion: Explicit collusion involves formal agreements among firms to control prices or production levels. Cartels are the most extreme form of explicit collusion, with firms openly coordinating their actions. While cartels can maximize profits for member firms, they often face challenges in maintaining cooperation.

- Cartels and Antitrust Laws: Cartels are perhaps the most notorious form of explicit collusion. These organizations consist of firms that agree to fix prices, limit production, or allocate market shares. Cartels can lead to artificially inflated prices and reduced consumer welfare. To counteract such anticompetitive behavior, many countries have stringent antitrust laws and regulatory bodies dedicated to enforcing them.

In the United States, for instance, the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act empower authorities to investigate and prosecute anticompetitive practices. Internationally, organizations like the European Union’s Directorate-General for Competition play a similar role in safeguarding fair competition.

Oligopoly Behavior and Decision-Making

The behavior of firms in oligopolistic markets is shaped by their strategic interactions and the anticipation of competitors’ responses. This often leads to intriguing decision-making processes that deviate from the norm.

- Price Leadership: In some oligopolies, one dominant firm may assume the role of a price leader. This firm sets prices, and others typically follow suit. Price leadership can bring a degree of stability to prices in the market.

- Kinked Demand Curve Model: The kinked demand curve model is a theoretical construct used to explain price rigidity in oligopoly. It suggests that firms face a demand curve with an elastic segment above the current price and an inelastic segment below it. As a result, firms may maintain existing prices to avoid potential adverse effects of price changes.

- Price Wars and Competitive Advertising: Oligopolistic firms are known to engage in competitive advertising and promotional activities. Price wars, where firms continuously undercut each other’s prices, can erupt. While price wars benefit consumers through lower prices, they can harm firms’ profitability.

Barriers to Entry in Oligopoly

Barriers to entry in oligopoly refer to the obstacles that make it difficult for new firms to enter and compete in an industry that is dominated by a small number of established firms. These barriers can take various forms and significantly affect market structure and competition. Here’s a detailed explanation of barriers to entry in oligopoly:

-

Economies of Scale

Economies of scale occur when a firm’s average cost of production decreases as it increases its output. In many industries, especially those with high fixed costs like manufacturing or infrastructure development, existing firms may have achieved economies of scale, allowing them to produce goods or services at lower costs.

Impact: New entrants often struggle to match the cost efficiency of established firms. Larger, well-established firms can produce more output at a lower cost per unit, giving them a competitive advantage. New entrants face higher average costs, making it difficult to compete on price.

-

Capital Requirements

Some industries require substantial initial capital investments in machinery, technology, or infrastructure. Established firms may have already made these investments, while new entrants face significant capital requirements to compete effectively.

Impact: High capital requirements act as a deterrent to new firms, limiting their ability to enter the market. Established firms may have easier access to financing or retained earnings, making it challenging for newcomers to raise the necessary funds.

-

Access to Distribution Channels

In certain industries, distribution networks and channels are controlled by existing firms. These channels may include retailers, wholesalers, or exclusive partnerships. New entrants may struggle to secure access to these distribution channels.

Impact: Without access to established distribution networks, new firms may find it difficult to reach customers effectively. Existing firms can leverage their relationships with distributors to limit the market presence of potential competitors.

-

Product Differentiation

Description: Oligopolistic markets often involve firms that have invested in building strong brand identities and customer loyalty. They may offer differentiated products or services that are difficult for new entrants to replicate.

Impact: New firms must invest in marketing, research, and development to create differentiated products or services. Building brand recognition and trust can be time-consuming and costly, making it challenging for newcomers to compete.

-

Regulatory Barriers

Regulatory barriers include government policies, licenses, permits, and intellectual property rights that restrict market entry. In some industries, firms may lobby for regulations that create entry barriers, such as safety standards or certification requirements.

Impact: Regulatory barriers can limit the number of firms allowed to operate in a market. Existing firms may use their influence to shape regulations in their favor, effectively blocking potential competitors.

-

Network Effects

Network effects occur when the value of a product or service increases as more people use it. Established firms benefit from larger customer bases, creating a natural advantage over new entrants.

Impact: New firms may struggle to attract customers initially because the established firms have already built large user networks. This effect is commonly seen in technology and social media platforms.

-

Predatory Pricing and Retaliation

Established firms with significant resources may engage in predatory pricing, temporarily lowering prices to drive new entrants out of the market. They may also retaliate against new competitors through aggressive pricing or marketing strategies.

Impact: The threat of predatory behavior can deter potential entrants, as they fear significant financial losses. This type of barrier can discourage competition and maintain the dominance of existing firms.

-

Brand Loyalty and Switching Costs

Firms that have built strong brand loyalty can retain customers even when competitors offer lower prices. Additionally, customers may face switching costs, such as time and effort, when transitioning to a new provider.

Impact: New entrants must overcome customer loyalty and offer compelling incentives to persuade customers to switch. These switching costs can make it challenging for new firms to gain a foothold in the market.

Understanding these barriers to entry is crucial for assessing the level of competition in oligopolistic markets and evaluating potential challenges for new entrants. These barriers can significantly affect market dynamics and influence the behavior of existing firms.

Government Regulation and Antitrust Policies

Given the potential adverse effects of oligopolistic behavior on competition and consumer welfare, governments around the world implement regulatory measures and antitrust policies. These measures aim to promote competition, prevent collusion, and ensure that firms do not engage in anticompetitive practices.

- Antitrust Laws: Antitrust laws, also known as competition laws, are enacted to safeguard fair competition in markets. They target anticompetitive behaviors such as price fixing, collusion, market allocation, and monopolization. The enforcement of antitrust laws can lead to legal action, fines, and the dissolution of anticompetitive agreements.

- Competition Authorities: Government agencies responsible for enforcing antitrust laws play a crucial role in monitoring and regulating oligopolistic behavior. These agencies investigate suspected anticompetitive practices, assess mergers and acquisitions for potential antitrust concerns, and promote competitive market conditions.

- International Coordination: Oligopolistic markets often span multiple countries, necessitating international coordination in antitrust enforcement. Organizations like the International Competition Network (ICN) facilitate cooperation among competition authorities worldwide to address global antitrust challenges.

Examples of Oligopoly

Examining real-world examples of oligopolistic markets provides valuable insights into the complexities of this market structure.

- The Global Automobile Industry: The automotive sector is a classic oligopoly, with a small number of major players dominating the market. Firms like Toyota, Volkswagen, General Motors, and Ford compete intensely through product differentiation, technological innovation, and global market presence.

- Soft Drink Industry: The soft drink industry is characterized by the duopoly of Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. These two giants fiercely compete in terms of branding, product diversification, and marketing campaigns, all while maintaining a stable pricing environment.

- Telecommunications: Telecommunications markets often exhibit oligopolistic features, with a handful of telecommunications companies controlling the industry. These firms invest heavily in network infrastructure and services while engaging in competitive pricing strategies.

What is Oligopoly | Characteristics | Graph | Types | Models | Barriers | Examples | PDF Free Download |

Conclusion

Oligopoly, with its intricate web of competition and cooperation, continues to shape the economic landscape across various industries.

Understanding the behavior of firms within oligopolistic markets and implementing effective regulatory measures is crucial for promoting healthy competition, consumer welfare, and economic growth.

As markets evolve and industries consolidate, the study of oligopoly remains a dynamic and ever-relevant field within economics.

See Also: What is Limit Pricing | Objectives | How It Works | Factors | Criticism