In economics, consumer surplus is a foundational concept that plays a pivotal role in understanding the dynamics of markets and consumer behavior. At its core, consumer surplus represents the economic benefit or gain that consumers enjoy when they are able to purchase goods and services at prices lower than what they are willing to pay. Let’s discuss consumer surplus in further more details.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus is an important concept in economics that represents the economic benefit or gain that consumers receive when they are able to purchase a product or service at a price lower than the maximum price, they are willing to pay.

It reflects the difference between what consumers are actually willing to pay for a good or service and what they actually pay for it in the market. Here are different definitions of consumer surplus:

- Consumer surplus is the monetary gain or economic benefit that consumers experience when they purchase a product or service at a price lower than the maximum price, they were willing to pay for it. It is the area between the demand curve and the market price in a graphical representation.

- Consumer surplus represents the surplus utility or satisfaction that consumers derive from the consumption of a good or service. It occurs when consumers are willing to pay more for a product than the actual market price, resulting in a surplus of value.

- Consumer surplus is a measure of the net gain in economic welfare that consumers obtain when they can purchase goods or services at prices lower than their individual valuation or willingness to pay. It reflects the additional utility or well-being consumers receive from their purchases.

- Consumer surplus is the difference between what consumers are prepared to pay for a product or service and what they actually pay. It is a measure of the economic surplus that accrues to consumers in a market and is a key concept in consumer theory.

- Consumer surplus is a concept that quantifies the economic benefit consumers derive from market transactions. It is calculated as the area between the demand curve and the price consumers pay for a good or service, indicating the excess value consumers receive.

Consumer surplus is a fundamental concept in economics used to assess the overall welfare and benefits that consumers receive from participating in markets. It is typically represented graphically in demand and supply diagrams and is an essential consideration in various economic analyses and policy evaluations.

How to Calculate Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus can be calculated by using the following formula:

Consumer Surplus = Willingness to Pay – Actual Payment

Consumer surplus can also be visualized graphically on a supply and demand curve. It is represented as the area between the demand curve (which reflects willingness to pay) and the market price, up to the quantity purchased.

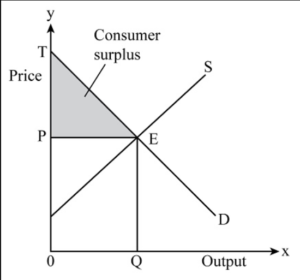

The Consumer Surplus Graph

The consumer surplus graph used to visually represent the concept of consumer surplus within a market. It illustrates the economic benefit or gain that consumers derive when they can purchase a product at a price lower than their willingness to pay.

Let’s break down the components and details of a typical consumer surplus graph:

- Axes: A consumer surplus graph typically has two axes: The horizontal axis (x-axis) represents the quantity of the product or service being considered. The vertical axis (y-axis) represents the price of the product or service.

- Demand Curve: The demand curve is a downward-sloping line on the graph. It represents the quantity of a product that consumers are willing to buy at various price levels. When price decreases, generally the quantity demanded increases. The demand curve reflects consumer preferences and their willingness to pay for the product.

- Market Price: The point where the demand curve intersects the vertical (price) axis represents the market price of the product. This is the price at which consumers are willing to buy a specific quantity of the product.

- Willingness to Pay (WTP): The willingness to pay represents the maximum price that consumers are willing to pay for a particular quantity of the product. It is usually indicated on the demand curve at a specific quantity.

- Consumer Surplus Area: The consumer surplus is represented as the area between the demand curve and the market price, bounded by the vertical (quantity) axis. This area is often shaded to distinguish it from the rest of the graph.

Now, let’s explore how the consumer surplus graph works in various scenarios:

- Below the Market Price

In this scenario, the market price (the actual price consumers pay) is lower than what consumers are willing to pay. This creates a consumer surplus. Difference between demand curve and market price known as consumer surplus.

- At the Market Price: When the market price aligns perfectly with consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP), the consumer surplus is zero. In this case, the entire area under the demand curve up to the market price is filled with consumer transactions at a price equal to their WTP.

- Above the Market Price: If the market price exceeds what consumers are willing to pay, the consumer surplus is negative, indicating dissatisfaction among consumers. In this scenario, consumers may purchase fewer quantities of the product, leading to a lower total utility compared to what they could have achieved if the price were lower.

Uses of the Consumer Surplus Graph:

- Policy Analysis: Economists and policymakers use consumer surplus graphs to assess the impact of policies, such as price controls, taxes, or subsidies, on consumer welfare.

- Market Efficiency: Consumer surplus graphs help determine whether markets are operating efficiently. When consumer surplus is maximized (usually under competitive conditions), it indicates efficient allocation of resources.

- Pricing Strategies: Businesses use consumer surplus analysis to understand consumer preferences and set prices to maximize profits while maintaining consumer satisfaction.

- Consumer Behavior: Consumer surplus graphs provide insights into consumer behavior, such as price sensitivity and the effect of price changes on consumer welfare.

The consumer surplus graph is a powerful tool for illustrating the economic benefit consumers gain from purchasing goods at prices below their willingness to pay. It’s an essential concept in economics that helps analyze market dynamics and make informed policy and business decisions.

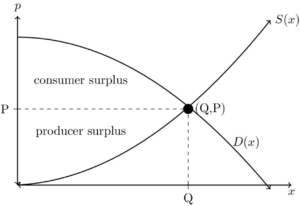

Consumer Surplus vs. Producer Surplus

Consumer surplus can be contrasted with producer surplus, which represents the gain that producers or suppliers receive when they sell goods or services at prices higher than their production costs.

Both consumer and producer surpluses contribute to the total welfare or economic well-being derived from a market transaction. Together, they constitute what economists call “total surplus.”

Consumer and producer surplus are essential concepts that shed light on the dynamics of markets, trade, and economic well-being.

Graph

Both terms represent gains or benefits derived from market transactions, but they arise from different perspectives within the market. Let’s see key differences between consumer and producer surplus.

-

Consumer Surplus: Maximizing Utility

Consumer surplus is a measure of the economic well-being that consumers experience when they can purchase goods or services at prices lower than their maximum willingness to pay. It reflects the additional satisfaction or utility that consumers gain from their purchases. Consumer surplus can be calculated using the following formula:

Consumer Surplus = Willingness to Pay – Actual Payment

Suppose a consumer is willing to pay $50 for a pair of sneakers but finds them on sale for $30. In this case, the consumer surplus is $20 ($50 – $30).

-

Producer Surplus: Balancing Costs and Revenue

Producer surplus, on the other hand, represents the gain or benefit that producers or suppliers receive when they sell goods or services at prices higher than their production costs. It signifies the difference between the market price and the minimum price producers are willing to accept for their products. The formula for calculating producer surplus is as follows:

Producer Surplus = Market Price – Minimum Supply Price

Suppose a producer can manufacture a product for $20 but sells it in the market for $40. In this case, the producer surplus is $20 ($40 – $20). Graphically, it is the area above the supply curve (indicating production costs) and below the market price, up to the quantity supplied.

Consumer Surplus and Producer Surplus

Consumer Perspective:

- Focus: Maximizing utility and satisfaction.

- Calculation: Willingness to pay vs. actual payment.

- Relationship to Prices: Consumer surplus increases as prices decrease.

- Policy Implications: Policies that lower prices or promote competition can increase consumer surplus.

Producer Perspective:

- Focus: Balancing production costs and revenue.

- Calculation: Market price vs. minimum supply price.

- Relationship to Prices: Producer surplus increases as prices rise.

- Policy Implications: Policies that support higher prices or reduce production costs can increase producer surplus.

Total Surplus and Market Efficiency

Consumer and producer surpluses together constitute what economists refer to as “total surplus.” Total surplus represents the net gain or benefit from a market transaction and reflects the economic welfare or well-being associated with that transaction.

Economists often use the concept of total surplus to assess market efficiency. In a perfectly competitive market with well-functioning supply and demand, total surplus is maximized, indicating that resources are allocated efficiently. When government interventions or market distortions occur, total surplus may be reduced, suggesting a loss of economic welfare.

Consumer and producer surpluses are fundamental concepts in economics that provide insights into market dynamics and economic welfare. While they represent different perspectives within a market transaction, both surpluses contribute to total surplus, which reflects the net benefits derived from exchanges in the marketplace.

It is important to understand the differences between consumer and producer surpluses for grasping the complexities of market behavior and the impact of economic policies on consumer and producer well-being.

Factors Influencing Consumer Surplus

Let’s discuss the factors influencing the consumer surplus below in detail.

-

Price Changes

One of the most significant factors influencing consumer surplus is changes in prices. When prices decrease, all else being equal, consumer surplus generally increases. This is because consumers can purchase more of a good or service for the same budget. Conversely, when prices rise, consumer surplus may decrease, leading to reduced purchasing power and satisfaction.

For example, during a sale or promotional period, consumers can often buy products at a discount, increasing their consumer surplus. On the other hand, rising prices due to inflation can erode consumer surplus, forcing consumers to pay more for the same goods and services.

-

Elasticity of Demand

The elasticity of demand measures how responsive the quantity demanded is to changes in price. It is a crucial factor in determining the size of consumer surplus. Here’s how it works:

Inelastic Demand: When demand is inelastic (PED < 1), consumers are not very responsive to price changes. In such cases, consumer surplus tends to be larger because even significant price increases result in only modest decreases in quantity demanded. Basic necessities like food and medicine often fall into this category.

Elastic Demand: When demand is elastic (PED > 1), consumers are highly responsive to price changes. Inelastic demand (PED < 1) often characterizes luxury goods or those with close substitutes. In such cases, consumers can quickly find alternatives if prices rise, limiting their consumer surplus.

-

Shifts in Supply and Demand

Changes in supply and demand conditions can significantly impact consumer surplus. When supply increases or demand decreases, prices tend to fall, leading to larger consumer surpluses. Conversely, supply shortages or increased demand can drive prices higher, potentially reducing consumer surplus.

For instance, during a bumper crop season, the increased supply of agricultural products can lead to lower prices at the grocery store, benefiting consumers. Conversely, during a natural disaster, increased demand for essential items like bottled water can push prices up, reducing consumer surplus.

-

Consumer Preferences

Consumer preferences, including tastes, preferences, and brand loyalty, also play a role in determining consumer surplus. Products that closely match consumers’ preferences are likely to generate higher consumer surpluses. Additionally, brand-loyal consumers may derive more satisfaction from purchasing products from their preferred brands, leading to larger consumer surpluses.

For example, a person who prefers a specific brand of sneakers may be willing to pay more for them, resulting in a larger consumer surplus when they find a discounted pair from that brand.

-

Income Level

Consumer surplus can vary with income levels. For essential goods like food and housing, lower-income individuals may have inelastic demand and smaller consumer surpluses because they spend a significant portion of their income on these necessities. In contrast, higher-income consumers may have more elastic demand for luxury goods, leading to larger consumer surpluses when prices decrease.

Consumer surplus is a dynamic concept influenced by various factors, including price changes, the elasticity of demand, shifts in supply and demand, consumer preferences, and income levels. Understanding these factors is essential for both consumers and businesses.

Consumers can make more informed purchasing decisions to maximize their consumer surplus, while businesses can adjust pricing strategies and offerings to cater to consumer preferences and demand elasticity. Policymakers also consider these factors when designing policies to enhance consumer welfare and promote economic well-being.

By recognizing the intricacies of consumer surplus, individuals and stakeholders can navigate the complex world of economic decision-making more effectively.

Limitations of Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus is a valuable tool in economic analysis, it is not without its limitations. Some criticisms suggest that it oversimplifies consumer preferences, assumes rational decision-making, and may not fully account for factors like consumer expectations and psychological effects.

-

Simplified Assumptions

Consumer surplus relies on certain simplifying assumptions that may not always hold in real-world situations. One of the most significant assumptions is that consumers have perfect knowledge of their willingness to pay for a product. In reality, consumers often have imperfect information about their preferences, and their willingness to pay can change over time due to evolving circumstances or new information. This assumption oversimplifies the complexity of consumer decision-making.

-

Rationality Assumption

Consumer surplus calculations assume that consumers are rational decision-makers who always seek to maximize their utility. While rationality is a fundamental concept in economics, it doesn’t always reflect human behavior accurately. In practice, consumers may make emotional or impulsive decisions that deviate from purely rational choices, affecting the accuracy of consumer surplus estimates.

-

Static Analysis

Consumer surplus is typically analyzed as a static concept, focusing on a single point in time. This approach does not account for dynamic changes in consumer preferences, incomes, or external factors that may influence consumer surplus over time. In a rapidly changing economic environment, static analysis may provide an incomplete picture of consumer welfare.

-

Ignores Non-Market Goods

Consumer surplus calculations primarily apply to market goods and services with well-defined prices. However, many aspects of life, such as clean air, a safe environment, and public goods, do not have clear market prices. Consumer surplus cannot accurately capture the value consumers place on these non-market goods, which are often essential for overall well-being.

-

Ignores Distributional Effects

Consumer surplus analysis often treats all consumers as if they benefit equally from a price reduction. In reality, the distribution of benefits can vary significantly among consumers. Lower prices may benefit some consumers more than others, leading to potential inequalities in consumer surplus distribution.

-

Ignores Externalities

Consumer surplus calculations do not account for externalities, which are the unintended effects of a market transaction on third parties. Positive externalities, like education or vaccinations, can generate significant societal benefits beyond individual consumer surplus. Failing to consider externalities can lead to an underestimation of the true benefits of certain goods and services.

-

Ignores Consumer Preferences Beyond Price

Consumer surplus is primarily concerned with price changes and their impact on consumer welfare. It does not consider other factors that influence consumer preferences, such as product quality, safety, environmental concerns, or ethical considerations. These factors can be equally important in determining consumer satisfaction and well-being.

-

Ethical and Cultural Considerations

Consumer surplus calculations do not account for ethical or cultural considerations that influence consumer choices. What one culture values highly may not be the same in another, and ethical concerns can impact the perceived value of goods and services. These considerations are often difficult to quantify and incorporate into consumer surplus analysis.

Consumer surplus is a valuable concept that offers insights into consumer welfare and market behavior. However, it is not a one-size-fits-all tool and should be used with awareness of its limitations.

Importance of Consumer Surplus

The concept of consumer surplus extends beyond national borders, especially in the era of international trade. Consumers in importing countries can enjoy lower prices and increased consumer surplus when they have access to a wide range of imported goods.

-

Consumer Surplus: A Global Perspective

Consumer surplus, at its core, represents the additional satisfaction and economic benefit that consumers derive when they can purchase goods and services at prices lower than their willingness to pay. This principle holds true whether consumers are making local purchases or engaging in cross-border trade.

-

International Trade and Consumer Surplus

International trade is a driving force behind the expansion of consumer surplus on a global scale. When countries engage in trade, consumers gain access to a wider range of products, often at lower prices than domestically produced alternatives. This increased variety and affordability of goods contribute to larger consumer surpluses.

For example, consumers in a landlocked country may enjoy significant consumer surplus when they can purchase exotic fruits from tropical regions through international trade, which would be otherwise unavailable or prohibitively expensive.

-

Lower Prices and Increased Variety

Consumer surplus in international trade is closely linked to the principle of comparative advantage. Different countries possess varying levels of efficiency in producing different goods. When nations specialize in producing goods in which they have a comparative advantage and engage in trade, consumers in both importing and exporting countries benefit.

Lower Prices: Importing countries often experience lower prices for goods produced more efficiently elsewhere. These reduced prices lead to increased consumer surplus for the importing nation.

Increased Variety: International trade allows consumers to access a broader array of goods. Consumers can enjoy the benefits of consumer surplus by having choices that align with their preferences and needs.

-

Examples of Consumer Surplus in Global Trade

Let’s consider a few real-world examples to illustrate the concept of consumer surplus in global trade:

Smartphones: Many electronic components of smartphones are produced in Asian countries with cost-efficient manufacturing processes. This global supply chain results in lower prices for consumers worldwide, expanding consumer surplus.

Automobiles: The global automobile industry relies on the production of parts in various countries. Consumers in different nations can benefit from the competitive pricing of vehicles due to global trade.

Textiles and Apparel: International textile and apparel trade offer consumers access to a wide range of clothing styles and designs at various price points, contributing to consumer surplus.

-

Consumer Surplus and Economic Growth

Consumer surplus derived from international trade has broader implications for economic growth. It stimulates consumer spending, encourages innovation, and fosters economic development. The increased availability of imported goods at competitive prices can enhance the overall quality of life for consumers.

-

Policy Considerations

Governments play a crucial role in shaping the extent of consumer surplus in global trade. Trade policies, tariffs, and trade agreements can impact the accessibility and affordability of foreign goods. Reducing trade barriers often leads to increased consumer surplus by promoting competition and lower prices.

Consumer surplus is not limited by geographical boundaries; it extends its reach across the globe through international trade. It represents the additional satisfaction and economic well-being that consumers derive from accessing a wider range of goods at competitive prices.

Consumer Surplus Explained | How to Calculate It | Graph | Factors | Limitations | PDF Free Download |

Conclusion

Consumer surplus is a fundamental concept in economics that sheds light on the benefits consumers derive from their choices in the marketplace. It not only helps us understand consumer behavior but also informs policymakers and businesses about the impact of their decisions on consumer welfare.

As consumers continue to make choices and seek value in the products and services they purchase, consumer surplus remains a critical concept that shapes the way we view and analyze economic transactions.